Suicide and Suicide Risk

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in youth ages 10 to 24 years old. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 57% increase in the national suicide rate for this population between the years of 2007-2018. While suicide in youth is difficult to predict, certain risk factors may be present that indicate the need to monitor a patient more closely for suicidal behavior, and make a referral to a mental health specialist.

Suicidality is a continuum that can range from the passive idea that it would be better to not be alive, to more specific and active ideas about suicide, to taking an action that an individual anticipates will end in death.

Role of the Primary Care Provider

Providers can take steps to recognize suicide risk factors and should regularly screen patients with clinical suspicion. Negative outcomes can be mitigated by helping promote protective factors (such as social connectedness) and improving effective problem-solving skills to manage stressors.

Pediatric primary care providers should recognize the relationship between suicide and mental health disorders in primary care visits. A small but significant number of patients with mental health conditions will experience suicidality. Some patients who don’t have a diagnosed mental health condition can also have suicidal ideation.

Providers should establish a collaborative relationship with the mental health specialists involved in the care of patients who are at risk of psychiatric emergencies to ensure that appropriate assessments and follow-up are provided when emergencies arise. Primary care providers should also know the steps needed to manage a concern for suicide risk with their patients. These steps include screening, assessing for severity, starting a safety plan and knowing the referrals needed.

1

Meet Isabella

Isabella is a 16-year-old female with a history of moderate depression who presents to the PCP's office for worsening depression. She reports crying every day and feeling hopeless about her life, as well as spending most of her time alone in her room. She cut herself with a paper clip for the first time last week when she was feeling overwhelmed. She denies that this was a suicide attempt, but she states that she wanted to “take the pain away.” However, she has had thoughts of wanting to die for two days. Her parents are very concerned.

1

Meet Noah

Noah is a 14-year-old male with a history of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus type one, ADHD, and depression who presents to the primary care provider's office for worsening mood. He reports high levels of irritability, periods of sadness, and little motivation to leave his room or complete his homework. He recently quit drama club and basketball because he did not find these activities enjoyable anymore. His mom is a single parent who works two jobs and is worried about Noah being alone at home every day. She is concerned that he is very depressed and has noticed that he has not been checking his blood sugar or using his insulin as he should.

Risk and Protective Factors

Risk Factors

Risk factors for suicide vary by age. Additionally, studies have shown that while suicidal thoughts and self-harm are more prevalent in adolescent females, rates of death by suicide are significantly higher in males in both adolescent and young adult populations. Recent studies have shown increases in major depression and psychological distress among youth aged 10-24, which are associated with self-harm and suicide attempts. Increases in adolescent suicide have also been linked to social media and internet use and may interact with other risk factors for certain individuals.

Common risk factors

Suicidal Ideation or Prior Suicide Attempt

One third of youth who experience suicidal ideation develop a suicide plan. Those who attempt suicide are at elevated risk of repeating the attempt. The presence of a past suicide attempt is viewed as the single most important static (i.e., non-changing) risk factor, and an important piece of history to inquire about in any evaluation for suicide risk.

Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behavior

While self-harm behavior performed without intent to die (such as most examples of cutting behavior in adolescents) is usually not life-threatening, it still represents a risk factor for suicide. Some individuals may miscalculate when engaging in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), especially when there are additional factors such as intoxication. Additionally, NSSI is believed to reduce inhibitions that humans normally have against harming themselves, which may then increase the likelihood of attempting suicide, and using lethal means when doing so.

Gender Identity and Sexual Minority Youth

Risk for self-harm and suicide attempts are up to six times higher for LGBTQ+ youth. This may be related to mental health issues or social factors. Youth who are rejected by family or peers due to sexual orientation or gender identity can experience disruptions to home and school environments that increase the risk of suicide.

Race and Ethnicity

In the US, American Indian/Alaskan Native individuals of all ages are at higher risk for suicide attempts and death by suicide compared to other racial and ethnic groups. Comparing white and Black individuals, the risk of suicide attempts and death by suicide has traditionally been viewed as higher among white individuals. However, recent statistics show a major increase in suicide among Black youth, indicating rising risk for these individuals. The reasons for these disparities are likely multifactorial, including especially high rates of stigma related to mental health conditions and care within communities, structural barriers to accessing care which disproportionately affect these communities, and stress because of direct experiences with racism.

Family History

Family history of suicide attempts or death by suicide is associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior in adolescents due to genetic and environmental factors. The risk for familial psychiatric disorders, modeling from a suicidal family member, or psychological stress from living with a family member with mental health issues may increase suicidality in youth.

Psychological Characteristics and Peer Influence

Certain psychological characteristics may increase the risk of suicidality. These include feelings of hopelessness, difficulty with problem solving, impulsivity, perfectionism, all-or-none thinking, impaired decision making, feeling defeated, or feeling that one is a burden to others or does not belong. Having peers who engage in self-harm has also been shown to increase risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults.

Psychiatric disorders

Mood disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder and anxiety are common in youth who attempt suicide. Those who do not receive treatment for these disorders are at an increased risk of self-harm and suicide. Psychosis is generally characterized by hallucinations of auditory or visual stimuli or delusions, which are fixed false beliefs, such as persistent paranoia. Psychosis is known to be an especially strong risk factor for suicidal thinking and behaviors and represents a serious mental health condition.

Physical Health Factors

Youth with chronic illness (such as diabetes, migraines, chronic pain, or epilepsy) or who have physical health diagnoses that create a state of poor health, are at increased risk for suicidal ideation. Disordered sleep can also be both a risk factor for, and a symptom of, mental health conditions.

Social Factors

Youth may experience significant cumulative stress from family losses, fractured peer or romantic relationships, bullying, academic pressure, abuse, neglect, food or housing insecurity, general poverty, or trauma that increases risk for mental health issues. Those who do not have the appropriate support to manage these difficulties are at increased risk of suicide. Another aspect of the social environment can be exposure to death by suicide, or suicide attempts by peers (including close friends or mere acquaintances), family members, or others (which may even include celebrities or fictional characters).

Substance Use

Substance use disorders are strongly associated with suicide risk, particularly when an individual has comorbid mental health disorders or interpersonal problems. Substance use impairs decision making and impulse control and can have significant psychopharmacological effects on the brain.

Clinical Pearl: Social Media's Impact

Most adolescents use social media. Potential benefits of social media include staying connected to friends and finding communities with similar interests and activities. However, social media also has potential risks. These risks include exposure to harmful or inappropriate content and interference with sleep, school, and other activities. Additionally, cyberbullying is a risk factor for mental health problems and suicide. Social media can also increase feelings of loneliness and inadequacy in some individuals. In patients who have other risk factors for suicide, discussing social media and other internet use can help providers understand how this may contribute to their overall risk.

Protective Factors

Protective factors often involve strengthening interpersonal relationships and developing skills that build resiliency and decrease negative outcomes for those at risk of suicide. Suicide prevention programs to increase protective factors should be tailored to those with significant risk factors, such as depression or previous suicidal behavior. For more detailed information on resiliency and suicide prevention programs visit Ohio RISE.

Peer Support

Adolescents are more likely to seek support from peers than adults and can benefit from positive peer influence. Local peer support programs such as Sources of Strength and Hope Squad, may be offered in a school or community settings.

Skills-based Training

Programs that increase problem-solving skills and effective coping strategies may reduce suicidal behavior in youth. School-based interventions to address these areas are associated with improvements in coping and cognitive abilities, as well as reduced suicide ideation. One such skills-based training that is used in the state of Ohio is the Signs of Suicide (SOS) Prevention Program.

Social Connectedness

Social connectedness is a strong protective factor for suicidal behavior, particularly in youth with comorbid depressive disorders. High levels of family and peer support and participation in religious communities have both been shown to increase social connectedness significantly.

Established Specialty Care

Risk of suicide is reduced when patients have connection to established mental health providers who can help treat mental health conditions, serve as a point of contact for concerns from the patient and caregivers about worsening suicidality and other symptoms and provide ongoing assessment/ reinforcement of measures to improve safety.

2

Isabella's Risk Factors

Isabella’s risk factors include suicidal ideation for the past two days; non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, although this appears to be new rather than chronic; major depression; and feelings of hopelessness.

2

Noah's Risk Factors

Noah’s risk factors include symptoms which are concerning for major depression, a chronic medical condition, and social factors which likely include strain in family finances and his caregiver’s availability for support and supervision. This constellation may lead to Noah feeling that he is a burden to others, which further increases his risk. Additionally, nonadherence to his diabetes care can quickly become dangerous, and even passively neglecting this can represent continuous access to lethal means of suicide, which is more rare in youth without diabetes.

Screening and Assessment

Screening

Preventing suicide requires both the capacity to detect indicators of suicide risk through screening and a strategy to evaluate those at risk to determine acuity so that urgent action can be taken when it is needed. As of 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) does not have a statement in support of universal suicide risk screening but indicates that primary care providers should be able to assess for suicide risk and act on it when recognized.

Universal Screening Using the ASQ

Due to the growing recognition that not all youth who die by suicide disclose suicidal thoughts to healthcare providers before attempting suicide, attention has grown for the need for universal screening for youth suicide risk. A free, validated tool studied by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) called Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) has been used in pediatric outpatient, inpatient, and emergency settings to detect suicide risk. The ASQ consists of four simple yes/no questions, with a fifth question indicating acuity in those who answer yes to one of the first four questions. It has been validated in children 8 years and older, with outpatient implementation more commonly being used in all patients 10 years and above.

Information about the ASQ, the ASQ itself, and the ASQ Toolkit can be found here: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials

The ASQ, intended to be posed verbatim and directly to the individual being screened, consists of these four questions:

- Q1: “In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?”

- Q2: “In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?”

- Q3: “In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?”

- Q4: “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?”

An answer of “yes” to any of these questions is a positive screen, and for those individuals, a fifth question is also asked:

- Q5: “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now?”

It is estimated that the ASQ takes about 20 seconds to administer.

Following-Up Positive Screenings

An affirmative answer to any of the questions indicates that additional assessment is needed to further understand the risk for suicide and determine next steps. An affirmative answer to question five signals current suicidal ideation and should be considered an emergency; it is important that the individual is considered high risk and in need of urgent safety measures until further evaluation occurs. Patients who answer “yes” to question five require evaluation by a provider who has expertise in assessing suicide risk. Depending on the setting, this may be a psychiatrist, a psychologist, an advanced practice psychiatric nurse, a social worker, a clinical counselor, or a member of a mobile crisis team. Evaluation in an emergency setting such as the emergency department may be necessary.

A positive screen, but with an answer of “no” to question five may or may not require evaluation by an expert, depending on the outcome of a follow-up assessment to the positive screen. Follow-up tools help the clinician to move through the process of screening to assessment to treatment planning with safety planning as needed.

Tools for Following-Up Positive Screenings

Two tools that can be used to assist in this evaluation include 1) the Brief Suicide Safety Assessment (BSSA) tool designed to follow-up positive ASQ screenings, and 2) the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). It is estimated that using one of these tools takes about 10 minutes and allows for further stratification of risk to assist in decision making; specifically, it can help determine if an evaluation by a provider with expertise in assessing suicide risk is needed, or if treatment and safety planning without emergency evaluation may be appropriate.

The BSSA designed for use with the ASQ can be found in the ASQ toolkit here: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/youth-asq-toolkit

The C-SSRS can be found here: https://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.healthcare.english. The version of the C-SSRS designated “Screener – Recent – With Triage – For Outpatient/Ambulatory” is appropriate to use in most outpatient settings as a screener or as the initial, 30-second step in administering the full version of the C-SSRS that begins with these 6 questions and may take 10 minutes to complete.

Clinical Pearl: ASQ Screening

Since the results of screening for suicide risk could indicate a concern that must be evaluated urgently, practices utilizing the ASQ or other suicide screening instruments must consider how positive screens will be consistently communicated to the provider responsible for further evaluating and managing potential risk. For instance, a practice which utilizes medical assistants or nurses to administer the ASQ before the primary service provider begins the visit must have an established flow for how a positive screen will be communicated to the provider.

3

Isabella's Screening

Isabella was administered the ASQ during her visit. She answered “yes” to questions one, two, and three, but “no” to questions four and five. Her PCP observed that this is a “non-acute positive screen” which warranted further discussion.

3

Noah's Screening

When interviewed alone, Noah admits to having thoughts of suicide. An ASQ was administered, and he answered “yes” to all questions, including question 5, “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now?” His PCP knew that action was needed.

Clinical Evaluation

Primary care providers must be prepared to incorporate general principles of suicide risk assessment into the care of individuals identified to be at increased risk for suicide, whether or not a provider or practice implements universal screening for suicidal ideation and uses tools such as the BSSA and C-SSRS to help characterize risk further.

Clinical Pearl: Suicide Screening Follow-Up

Situations other than a positive suicide risk screen that should prompt a provider to inquire about suicidal thoughts include: 1) concerns related to recent suicidal thoughts, statements, or behaviors brought up by the patient, caregiver, or other sources of collateral information such as school personnel; 2) the presence of self-harm behaviors by a patient; 3) current depressive symptoms or statements indicating hopelessness; and 4) a dramatic change in social environment accompanied by significant distress (examples may include loss of a stable home environment, family financial stressors, loss of a significant relationship school difficulties, bullying, known suicide event within a school or community, or legal problems).

Presence of Suicidal Thoughts

When screening for the presence of suicidal thoughts during a clinical interview conducted based on a raised index of clinical suspicion rather than after using the ASQ as a universal screener, questions one through three from the ASQ can still be used, either verbatim or paraphrased (e.g., changing “in the past few weeks” to “recently” or “lately”).

Frequency

If suicidal thoughts are present, inquire about their frequency, e.g. “How often have you been having those thoughts?” It may be helpful to specify a timeframe (e.g., the past two weeks) and offer choices such as several times a day, once or twice a day, a few times per week, etc. Inquire about when these thoughts occurred most recently, including asking about their being present at the time of the interview.

Intensity and Duration

It can be helpful to ask about how intense suicidal thoughts are and how long they last (e.g., days at a time, all day, a few hours, a few minutes, a fleeting thought for just a few seconds, etc.).

Plan

For individuals with suicidal thoughts, inquire about the presence of a plan and ask for information about any details if a plan is present. Sample questions include, “Have you been thinking about how you might do this?” or “Do you have a plan to kill yourself?” You can follow up this with “What is your plan?” or “If you were going to kill yourself, how might you do it?” If they say they have a plan but then refuse to disclose it to you, this is a very serious sign of risk.

Clinical Pearl: Unwillingness to Disclose

Some patients endorse having a plan for suicide but are unwilling to disclose the plan. This is a concerning finding indicating an elevated risk and it will make it difficult to safety plan effectively. Such patients may require a full suicide safety evaluation in an emergency setting, with the possibility of hospital admission.

Past Behavior

Inquire about past episodes of self-injury and suicide attempts, and follow-up affirmative responses. A sample question is: “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” and, if yes, ask questions about when, how, and why. Ask specifically about what the individual wanted or expected to happen, and whether they received medical attention and told anyone about the episode. Inquire about past episodes of preparing for a suicide attempt, even if suicide was not ultimately attempted. A sample question is: “Have you ever started to do anything or prepared to do anything to end your life?” Follow up affirmative answers by asking when and asking what stopped the individual. One type of preparatory action is obtaining means for a suicide attempt, such as pills, a gun, the means for strangulation/hanging, going to a high place to possibly jump. Preparatory actions might also be researching specifics of suicide methods or taking steps in anticipation of the individual being dead, such as giving away valuables or writing or recording a suicide note, message, or text. A final type of preparatory action is one taken to prevent discovery of the suicide attempt before it is lethal, such as making plans to be away from caregivers so that the suicide attempt can occur with minimal likelihood of interruption.

Symptoms

In individuals with suicidal thoughts, assessing for the presence of psychiatric symptoms is important. Assess for symptoms of major depression, significant anxious distress, substance use, aggression, psychosis, and impulsivity. While suicidality can certainly be present without accompanying aggression, aggression is an independent risk factor for death by suicide.

Social Supports and Reasons for Living

When suicidal thoughts are present, inquire about supports. For example, “Is there an adult you can trust to talk to about this?” Ask about reasons to stay alive, for example, “What are some reasons you might NOT kill yourself?”

Stressors

Inquire about factors contributing to suicidal thoughts or overall emotional state, such as family, school, bullying, and suicide examples known to them. Example questions: “Are there situations at home that are hard to handle? Do you ever feel so much pressure at school that you cannot take it anymore? Are you being bullied or picked on? Do you know anyone who has killed themselves or tried to kill themselves?”

Continuum of Suicidal Thoughts

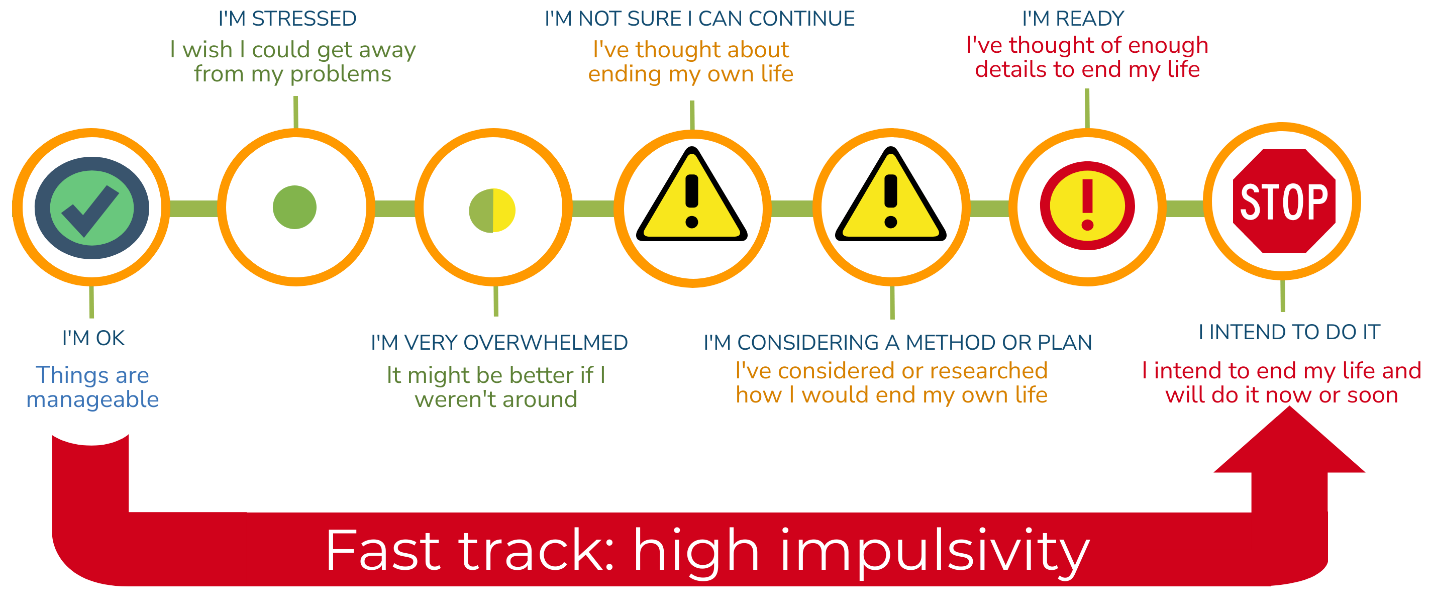

Since suicidal thoughts may precede suicide attempts and death by suicide in some individuals, it is important to identify individuals who are experiencing them. However, in terms of risk of death by suicide, suicidal thoughts themselves exist on a continuum, where the risk of suicidal behavior occurring is much higher when there is detailed planning, preparatory actions, and/or intent to carry out a suicide plan. One way to conceptualize this continuum is depicted below:

The continuum proceeds from left, corresponding to minimal risk of suicide, to the right, corresponding to extremely high and imminent risk. This helps explain why assessment of risk in individuals experiencing suicidal thoughts include asking about methods considered and the degree of detailed planning. A nearly universal experience, not particularly associated with risk of suicide, is a wish to escape problems or stressors. Slightly further on the continuum is the experience of feeling so overwhelmed (by emotions or stressors) that the individual feels that death might be advantageous. This line of thought, without thoughts of taking action to end one’s life, is sometimes termed passive suicidal ideation. Next on the continuum is having thoughts about suicide, without having seriously considered any methods to do it. Progressing along the continuum, individuals may have considered a plan, to a varying degree of specificity. At some point, the individual may have considered the plan in enough detail to be prepared to carry it out (.for instance, a plan of how and when to access a firearm to attempt suicide, or access pills needed for a lethal ingestion). At the extreme end of the continuum, a patient might have a detailed plan with the intent to carry it out - these individuals are on the cusp of attempting suicide unless prevented from doing so.

Normally, movement along the continuum is gradual, giving opportunities for the patient to reach out for help and to utilize coping skills or take advantage of protective factors before they are on the extreme right side of the continuum. However, there are some factors which make individuals at a higher risk of moving quickly to the extreme right side of the continuum.

These “fast track” factors include impulsivity from substance use, bipolar disorder, ADHD, or traumatic brain injury; a significant history of trauma; and young age (that is, pre-adolescence) and/or intellectual disability. It is important to carefully evaluate suicidal thoughts in these patients, even if they deny suicide planning or intent, given their increased risk of moving quickly along the continuum.

Clinical Pearl: Pre-Adolescent Suicide Attempts

While the rates of death by suicide are much lower in pre-adolescents than adolescents, when pre-adolescents attempt suicide by lethal means, there may be less warning and, thus, less opportunity to intervene.

Clinical Pearl: Impulsivity in Pre-Adolescents

Impulsivity of behavior, or acting without fully considering the consequences, is something that gradually lessens over time from childhood through adulthood. Pre-adolescents are more impulsive than adolescents, which helps explain why, although they attempt suicide less often, when they do, there may be less warning. Similarly, adolescents are, in general, more impulsive than adults. They also tend to have more difficulty than adults seeing current stressors as temporary while having intense emotional experiences of these stressors. Taken together, these factors mean that adolescents may be especially vulnerable to viewing their circumstances as hopeless, and acting impulsively to end their distress, putting them at risk of suicide.

4

Isabella's Suicidal Thoughts

After a non-acute positive screen on the ASQ, meaning she answered “yes” to at least one of questions 1 through 4 but “no” to question 5, the PCP met with Isabella alone to discuss her symptoms and ask more detailed questions about her suicidal thoughts. The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) screener was used to further characterize her risk. Isabella answered “yes” to wishing to be dead (question 1) and to having suicidal thoughts (question 2), but “no” to having thought about a method (question 3), having intent to act on suicidal thoughts (question 4), and having a specific plan with intent to carry out this plan (question 5). She was also asked if she has ever prepared to, started to, or done anything to end her life (question 6) and she answered “no.” Recalling the continuum of suicidal thoughts, the PCP placed her in the middle of the continuum, having had thoughts of suicide but without having considered a method. No common factors that would be expected to result in a “fast track” to high suicide risk seemed to be present. Based on her answers and further information obtained about her positive answers, the patient appeared to be in need of treatment, but in the low-risk category for imminent death by suicide.

4

Noah's Suicidal Thoughts

The PCP met with Noah alone and asked follow-up questions about his suicidal thoughts. Noah’s suicidal thoughts were occurring daily, and he had considered methods of suicide such as giving himself too much insulin, taking a bottle of acetaminophen, or trying to find a way to access the handgun that the family kept locked. He had researched how many acetaminophen tablets he would need to take and had considered when he could access the medicine cabinet unnoticed if he decided to do it. Remembering the continuum of suicidal thoughts, the PCP recognized that Noah was already quite far to the right on the continuum, having identified lethal methods and considering details of a future suicide attempt. Noah seemed to appreciate the PCP being concerned but not panicked, and overall seemed relieved to share this information.

Treatment

MYTH: All youth with suicidal thoughts need to be admitted to an inpatient unit.

Fact: All youth with suicidal thoughts and behaviors should have an evaluation that seeks to further characterize risk to safety, should receive a level of care appropriate to that risk, and should receive treatment for underlying conditions.

Safety Planning

Whenever suicidal thoughts are present it is important to create a safety plan with the patient and family. A safety plan can be simple or complex and can be completed by any member of the multidisciplinary care team. The essential elements of a safety plan include a list of trusted contacts, ways to increase supervision of the patient at times of distress, and instructions for removing access to lethal means in the home. The list of trusted contacts should include phone numbers for adults or for places the patient can contact when in distress. This list should be made with direct input from the patient and should be tailored to the patient’s needs, comfort, and location. The restriction of access to lethal means should be done through a conversation with the family present in the home. This conversation should include directives and problem solving on how to lock up medications, sharp objects, and other potentially lethal items. Also, it is imperative to discuss access to guns and other weapons. Firearms should be locked away, unloaded, with ammunition also locked away in a separate location. The patient should have no access to weapons or firearms. This is a crucial component to safety planning.

More complex safety plans can include addressing modifiable risk factors for suicide, identifying warning signs for mental health decompensation as well as coping skills the patient can use when upset, and interventions others can offer to help the patient when distressed. For more ideas on how to safely store firearms and other lethal means, visit the link for Ohio Store It Safe.

Crisis Support Lines

- 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, formerly the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline provides 24/7, free, and confidential support.

- Text the word “safe” and your current location (address, city, state) to 4HELP (44357).

- Within seconds, you will receive a message with the closest Safe Place site and phone number for the local youth agency.

- For immediate help, reply with “2chat” to text interactively with a trained counselor.

My Suicide Prevention Apps

- "A Friend Asks" – a smartphone app to help a friend (or yourself) who may be struggling with thoughts of suicide

Get Immediate Help

If families call with a report of a suicide attempt or dangerous behavior, they should be referred to the nearest emergency room or instructed to call 911. If patients can safely be brought into the office, they should be directed to do so.

When a safety assessment has been completed in the office and the child is deemed unsafe to return home, the patient should be referred to the emergency room. Many times, families are comfortable transporting their child and this is acceptable if the clinician judges this to be safe. Less frequently, patients require medical transport from the primary care office to the emergency room to ensure safety.

If a patient is at home with safety concerns, but the family cannot transport them to the office or to the emergency room, mobile crisis may be called to help with assessment in the home. Many counties across the state have a mobile crisis team in place. This team of trained mental health professionals are available to assess children and adults in mental health crisis in their home environment.

Relationships Between Antidepressants and Suicide Risk

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the main evidence-based medications for the treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. They are indicated when anxiety or depression begins to have moderate to severe impact on the patient’s functioning. They are proven to be an effective component of a comprehensive plan of care. However, these medications and other antidepressants come with a boxed warning from the FDA stating that these medications have been associated with increased suicidality in adolescents and should be used with caution.

Since these concerns were raised in the early 2000s, further studies and analysis have shown that the link between the SSRI medications most used to treat youth depression and anxiety disorders- fluoxetine, escitalopram, and sertraline- and suicidal thoughts and behaviors is very weak. SSRI medications do not appear to cause adolescents to become suicidal and there is limited evidence to support the boxed warning. Studies showing that SSRIs are effective in treating depression and anxiety suggest that they are protective against suicidality. The potential benefits of adding SSRI treatment for moderate to severe anxiety or depression treatment outweigh the minimal potential risk that patients will experience increased suicidal ideation. It is important to talk about the boxed warning with families during medication management visits.

Clinical Pearl: Inpatient Psychiatric Hospitalization

Some youth with suicidal thoughts and behaviors will require an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, with a goal of stabilization on a locked unit which has the means to observe patients closely and a treatment environment designed to prevent access to means of self-harm. This level of care is often selected for identified patients following an evaluation in an emergency department, where a provider trained in suicide risk assessment considers what level of care is most appropriate. If an emergency department clinician determines that inpatient psychiatric hospitalization is necessary, they will work to identify a facility that has an appropriate, available bed and can immediately accept the patient for care. Once a patient has been accepted for inpatient admission, they will be sent to the facility by way of medical transport, so that close observation, care, and support can be provided en route.

5

Isabella's Treatment

The primary care provider (PCP) felt that it was likely that Isabella’s suicidal thoughts, non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, and depressive symptoms were all linked. Isabella completed a PHQ-9 form to screen for depression which suggested that she was experiencing moderately severe major depression, and this matched the PCP’s clinical impression about her functional impairment. The PCP praised Isabella for her bravery in communicating how she was feeling and conveyed optimism that there is treatment that can help her feel better. The PCP advised that expanding her care team to include a provider with expertise in mental health would be a good idea. After discussing possible treatment plans, Isabella and her mother agreed that the combination of psychotherapy and SSRI medication, which was recommended by the PCP, was a good idea. The PCP worked with Isabella and her mother on a brief safety plan.

5

Noah's Treatment

Noah, his mom, and his provider had a discussion regarding his high risk for death by suicide. The decision was made to refer Noah to the local emergency room for a full assessment by a mental health professional. His mom felt safe to take him to the hospital, and the PCP's office called the emergency department to inform them of Noah’s expected arrival. The PCP asked Noah’s mom to call and let the office know the outcome.

Follow-up

Patients should be continuously assessed for suicidality after the initial presentation. When a patient has had a previous attempt or suicidal ideation, they are at an increased risk of future suicidality. Patients should be screened for suicidality at their next follow up visit, at their ongoing well child checks, and whenever there is concern for declining mental health. It is also essential to continue to treat the underlying disorders and address life circumstances that may be contributing to suicidal ideation. Frequent follow up appointments are recommended if a patient is having an acute exacerbation of major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder. During these follow ups, primary care providers should be assessing the patient and providing appropriate interventions as necessary. These should include brief interventions to enhance resilience, collaboration with other members of the patient’s care team, and may be in concert with medication management.

The vast majority of children and teens who experience suicidality should be referred to receive psychotherapy in addition to being seen frequently by medication providers, school counselors, and other mental health workers as part of their care team. Primary care providers (PCPs) should communicate with all the mental health providers during ongoing suicide risk management like they would with medical subspecialists. Other members of the care team often have insights into why patients are not improving or why they may be in crisis. Conversely, other care team members can be unaware when patients present to their PCP in crisis and should be informed of such observations. Collaboration between PCP’s and all members of the mental health care team is a best practice that can ensure all parties remain on the same page when providing treatment.

When suicidality occurs in a patient it can be overwhelming for clinicians who do not deal with the issue on a regular basis. PCPs are the front line for preventing deaths by suicide in young people. The best preventative medicine for youth suicidality is a plan that consists of frequent follow up appointments, close monitoring of symptoms, collaboration with the specialist care team, and relationship building with patients and families. This approach is not unlike managing other chronic health conditions, which is exactly what PCP’s do best.

Caregiver and Family Support

Family of youths at risk for suicidal behavior play a key role in recognizing and responding to suicide risk.

Strategies for Supporting Youth at Risk for Suicide

- Learn about common risk factors for suicide and identify areas where the youth may be struggling.

- Identify ways to promote protective factors, such as connecting youth with peers, family, community groups, and/or training to increase problem-solving and coping skills.

- Assist youth in accessing appropriate mental health services. Talk with the youth’s primary care provider about options in your area and obtaining referrals.

- Assist youth in adhering to prescribed medication or treatment regimens.

- Create a family safety plan to prepare for crisis events.

- Talk to youth in a non-judgmental way about changes in mood or decreased interest in friends and activities.

- Let them know why you are concerned.

- Ask them directly if they have thought about suicide.

- Be empathetic to their struggles.

- Validate their feelings.

- Encourage them to speak with their mental health provider or a crisis support counselor.

Clinical Pearl: Black Box Warning

The discussion of the boxed warning about suicidal thoughts and behaviors may cause some patients and families to be nervous about pharmacotherapy. It is better, however, for them to have the topic broached by a provider they can trust instead of obtaining information from less reliable sources. Some of these resources may have an anti-medication agenda and spread false information. In discussing the boxed warning with patients and families, it can be helpful to link the discussion to the need to notify a provider if suicidal thoughts or behaviors develop or intensify, regardless of the reason. For instance: “I bring this up not because I think the medication will cause you to be suicidal – that doesn’t seem at all likely to happen – but because if you were having suicidal thoughts (or more frequent or intense suicidal thoughts), it would be important for you to talk with an adult you trust, like me, your therapist, or your caregiver about them.”

6

Isabella's Safety Planning

A safety plan was developed that listed Isabella’s personal risk factors, warning signs, and coping skills. The primary care provider (PCP) also talked with her parents about developing a plan to restrict access to lethal means, including firearms, in the home. Isabella then made a written list of phone numbers of trusted adults in her life. Lastly, she was able to talk with the PCP and her parents about what they could do to best help her in times of distress. Isabella was started on fluoxetine 10 mg daily for her severe depression, referred to a psychotherapist, and instructed to follow up in the PCP's office in one week.

6

Noah's Safety Planning

After assessments were conducted by a social worker and a psychiatrist, Noah was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for further stabilization and care. During the inpatient hospitalization, the treatment team worked on enhancing coping skills, family communication, and a robust safety plan for home. The handgun was removed from the home and a lockbox for medication and a plan for safely managing Noah’s insulin were discussed during the hospital stay. Noah’s treatment team also ensured that outpatient mental health follow-up resources were available upon discharge. At the next visit to the PCP’s office, the PCP inquired about the safety plan that had been made prior to discharge from the hospital and confirmed that it was working well for Noah and his family.

Resources

Zero Suicide Framework for Health and Behavioral Health Care Systems

For systems dedicated to improving patient safety, Zero Suicide presents an aspirational challenge and practical framework for system-wide transformation toward safer suicide care.

American Academy of Pediatrics Blueprint for Youth Suicide Prevention

Designed to support pediatric health clinicians in advancing equitable youth suicide prevention strategies in all settings where youth live, learn, work, and spend time.

Blueprint for Youth Suicide Prevention

The Ohio Department of Mental Health & Addiction Services (OhioMHAS) seeks to support local mental health systems that foster resiliency at all levels, including mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention, with the ultimate outcome of resilient people, families, and communities. The OhioMHAS website has links to educational resources and ways to connect with providers.

School Aged Youth Mental Health

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

Suicide Safety: Precautions at Home

Mental Health America

Talking to Adolescents and Teens: Starting the Conversation

NAMI Ohio

Healthychildren.org

10 Things Parents Can Do to Prevent Suicide

En Español: Diez cosas que los padres pueden hacer para prevenir el suicidio

Which Kids are at Highest Risk for Suicide?

En Español: ¿Qué niños corren mayor riesgo de suicidio?

How to Help Children Build Resilience in Uncertain Times

En Español: Cómo ayudar a los niños a desarrollar la resiliencia en tiempos inciertos

The Jason Foundation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is suicide preventable?

Suicide is often preventable if individuals who exhibit warning signs are identified as needing support and can receive the care they need.

Is it okay to ask someone directly if they are having suicidal thoughts?

Anyone who is part of a youth’s school, peer group, community, or family can help identify and support youth at risk for suicide. Asking them about suicide is not suggesting, but rather intervening in the behavior.

Should special considerations be given to finding a provider for an LGBTQ+ youth at risk for suicide?

Many LGBTQ+ youth experience discrimination and rejection that can be risk factors for suicide, particularly if they are not accepted by their parents and family. It is important that medical providers and therapists for these youth be affirming, accepting, and supportive of their identity and personal choices.

References

-

Curtin, S. (2020, September 11). State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24: United States, 2000 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr69/nvsr-69-11-508.pdf

-

Miron, O., Yu, K. H., Wilf-Miron, R., & Kohane, I. S. (2019). Suicide rates among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2000-2017. JAMA, 321(23), 2362–2364. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5054

-

Thapar, A., Pine, D. S., Leckman, J. F., Scott, S., Snowling, M. J., & Taylor, E. (2015). Rutter's child and adolescent psychiatry (6th ed.). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118381953

-

Sisler, S. M., Schapiro, N. A., Nakaishi, M., & Steinbuchel, P. (2020). Suicide assessment and treatment in pediatric primary care settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 33(4), 187– 200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12282

-

Lu, C.Y., Penfold, R.B., Wallace, J., Lupton, C., Libby, A.M. & Soumerai, S.B. (2020). Increases in suicide deaths among adolescents and young adults following US food and drug administration antidepressant boxed warnings and declines in depression care. Psychiatric Research & Clinical Practice, 2(2), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20200012